This is Part 2 of a three-part series titled: “Michael Barnard: Exposing Anti-Hydrogen Media Bias – Part 2 of 3 – Heavy Ground Transportation: Rail, Bus, and Truck.” In Part 1, the topic and thesis statement for the series were presented, along with Barnard’s curriculum vitae and journalistic style. We also examined how Barnard fits into the genesis of anti-hydrogen media narratives that began in October 2013. In this section, we examine how Barnard misleads readers into viewing batteries and hydrogen as mutually exclusive technologies rather than complementary ones. In “Part 3 of 3 – Critical Minerals, China’s Coal Economy, and Fair Trade” we explore the foundation of the new energy economy and China’s near-total monopoly on raw mineral production and metal refining, which supports the battery, magnet, solar PV, silicon microchip, and electric motor industries. Each part of this series stands alone, but the report was originally written as one long piece, and was later divided into three parts to make reading easier.

Rail, Bus, and Trucks – Hydrogen & Batteries Work Together – It’s Not “Either/Or”

Heavy ground transport — rail, bus, and trucks — is far from settled science when it comes to propulsion technology. While battery buses, for example, have completely or nearly completely replaced diesel buses in Chinese cities like Shenzen, Beijing, and Shanghai, diesel buses continue to dominate areas like intercity coach routes that zero emissions technologies have not yet been able to penetrate. Barnard focuses on successes of battery technology in certain areas and then extrapolates those adoption rates or trends to sectors where they are far less practical, like in my country the USA or in his own country Canada where corridor capacity is completely different than China or Europe.

Each technology brings advantages in different contexts, and all will play roles in the transition to sustainable transport over the coming decades. Batteries are well suited for short to medium range routes with predictable duty cycles. Hydrogen offers flexibility for long haul routes and heavy loads. Diesel remains competitive where infrastructure or technology gaps persist, and even diesel technologies continue to advance. In the sections that follow, we will examine how rail, bus, and truck markets are each adopting new propulsion technologies in ways that reflect their unique market demands, showing that a multi-technology approach is not just inevitable but necessary. These viewpoints expressed by RMP and over 60 countries with national hydrogen policy frameworks including all eight G8 members stand in stark contrast to Barnard’s insistence that the question of propulsion technologies for heavy ground transport has already been answered in 2025.

Rail – The Economics Barnard Glosses Over

Rail is perhaps the clearest example of why Michael Barnard’s “batteries, wind, and solar for everything” narrative falls apart under scrutiny. He regularly points to Europe’s extensive electrified rail network as a model that the world should follow, while glossing over the very different realities in places like the United States. Companies like Stadler and Siemens, often seen as the dominant players in both hydrogen and battery rail, are deliberately pursuing multiple propulsion solutions because different rail segments have different needs. Short and medium range regional lines are often best suited for battery electric multiple units, but long rural routes and heavy freight corridors require the endurance and flexibility of hydrogen or advanced diesel hybrids.

China itself demonstrates this nuance. The country is rapidly electrifying its busiest mainlines, particularly its coal transport corridors, while also deploying battery hybrid locomotives for secondary lines and branch routes. This approach works in China because of the extremely high density of freight on key corridors, where catenary is cost-effective. At the same time, batteries provide an off-wire option for lower density lines where wiring would not pay off.

The United States could not be more different. According to the Association of American Railroads (AAR), fully electrifying the 139,000-mile freight network would cost more than one trillion dollars — roughly half a century of net income for all six Class I railroads combined. Beyond cost, it would require forty to fifty terawatt hours of new electricity every year, equivalent to adding multiple nuclear plants or thousands of solar farms just to power freight rail [14]. On top of that, the long distances and sparse traffic densities across much of America’s rail system make overhead wires an operational nightmare. Routes like the Crescent Corridor, stretching 1,400 miles from New York to Louisiana, cut through rural heartlands where the economics of catenary wires simply collapse.

Yet in a podcast with his friendly & frequent guest David Cebon of the [anti] Hydrogen Science Coalition, Barnard declares “It’s quite remarkable that they’re [AAR] so out of step with the obvious solution” by not pursuing catenary electrification.” Cebon agrees emphatically remarking “It is quite shocking.”[15-1] Cebon himself acknowledged that catenary would cost roughly £1 million per kilometer (about $2 million per mile)[15-2], but neither seemed willing to reconcile that number with America’s 139,000 miles of track. This is precisely how Barnard misleads: he highlights how one technology works in a specific market, then universalizes it as if geography, economics, and infrastructure realities do not matter. Worse than just having it wrong, Barnard scoffs and exclaims “Putting a pantograph on the roof [of all trains] to feed those electric motors is a trivial addition. And dropping a container car of batteries just behind the locomotive to feed those motors is a trivial change”[16-1]. Dismissing the challenges of implementing catenary rail in the USA or Canada as “trivial” reveals more about Barnard’s misunderstanding of energy & economics than anything else.

The arrogance of how Barnard frames planning decisions for rail is not only misleading, but damaging. When Barnard waves away the concerns of experts like the Association of American Railroads and calls solutions “trivial” from behind a microphone in Vancouver, he undercuts serious discussions about how decarbonization must actually unfold in complex and varied markets. The truth is straightforward: rail sustainability is not settled science, and the future will not be batteries or catenary wires alone. Hydrogen and hybrid solutions will play indispensable roles, especially in countries like the United States where long distances and freight-heavy networks make catenary electrification impractical.

Michael Barnard often builds his case by highlighting examples that appear to support his argument while leaving out the context that makes them work. His use of the Trans-Siberian Railway is a good illustration in his written version of his views on rail. Yes, it’s electrified, and yes, it runs across some of the harshest terrain in the world. But what he leaves unsaid is why Russia electrified in the first place. For the Soviets — and later the Russian Federation — the economics were straightforward: burn cheap, low-value coal at home to power trains, and use those trains to move oil and other resources to market, where they command hard-currency export prices. Sustainability and zero emissions had nothing to do with Russia’s decision making. The decision Russia made was about maximizing fossil fuel export revenue and strategic resilience on cheap unregulated coal burning, not greening the rail sector; quite the opposite of a sustainable decarbonization strategy to brag about on a site called Cleantechnica. That calculus makes sense for Russia’s fossil fuel–driven economy & absence of care about harmful emissions at home or abroad, but it has little in common with America’s situation or goals. In other words, citing the Trans-Siberian as “proof” that rail should be electrified with catenary everywhere ignores the fact that different countries face very different economic incentives. Good policy weighs those differences — it doesn’t just follow a non-accredited blogger’s one-size-fits-all narrative.

What’s truly remarkable about the conversations between Barnard and Cebon in podcasts 5 and 6 isn’t the Association of American Railroads’ position, but how casually they dismiss and mock expert research that doesn’t align with their narrative. I recommend listening to the podcasts [links in footnotes] rather than just reading the Cleantechnica articles — the tone on the podcast says as much as the words. You’ll hear scoffs of exasperation, arrogance, and name-calling directed at anyone who questions the narrative. It’s Barnard and Cebon who are out of step with basic economics, not the AAR. And this isn’t an isolated case: as you’ll see throughout this three-part series, Barnard routinely mocks experts when their analysis doesn’t fit neatly into his storyline. With that in mind, let’s turn to another example — Barnard’s forecasts for buses.

Buses – What Barnard Leaves Out of the Picture

Michael Barnard’s publishing history reveals a clear and consistent pattern: hydrogen buses are cast as villains, while battery buses are shielded from comparable scrutiny. Out of his more than 1,140 articles, “bus” ranks as the fourth most common keyword in his post titles behind keywords hydrogen, Tesla, and China—a signal of both his obsession and his agenda. Time and again, Barnard seizes on any negative headline about hydrogen bus projects, magnifying it into proof that the entire technology is a dead end, while news about the setbacks of battery-electric buses either slips past his radar or is reframed to fit his narrative. In Barnard’s worldview, hydrogen buses are not just an alternative technology; they are a threat to the storyline he has invested in, and therefore anyone who defends or even acknowledges a role for them quickly becomes an adversary in his writing.

This bias is not confined to isolated articles, there’s a clear pattern. A hallmark of Barnard’s method is the way he uses his podcast as a staging ground, where he can float narratives with like-minded guests, then reinforce those narratives through a rapid cascade of follow-up pieces at Cleantechnica. The CUTRIC case in Brampton Ontario is one of multiple examples that illustrates this well. When the Canadian transit research group recommended a blended fleet of battery-electric and hydrogen fuel cell buses for the city, Barnard and his friendly guest Michael Raynor discussed it at length on his podcast[3], ridiculing the report like schoolyard bullies. That podcast conversation then spawned no fewer than 14 separate Cleantechnica articles focused on hydrogen buses[17-1 to 17-14] in the Greater Toronto Area, each one reinforcing Barnard’s anti-hydrogen framing. Brampton thus becomes more than just a local transit story—it serves as a microcosm of Barnard’s playbook for shaping perception, smearing hydrogen, and elevating battery buses as the only acceptable solution.

The Brampton example also reveals something more personal: Barnard was triggered precisely because this was happening in his childhood backyard. Having built his reputation on portraying hydrogen buses as impractical failures, the idea that a hometown Canadian city in the Greater Toronto Area would move forward with a plan that included hydrogen directly challenged his narrative. Instead of engaging with the CUTRIC study on its merits, he reacted by doubling down—leveraging both his podcast and subsequent articles to paint hydrogen buses as inherently flawed, while casting doubt on the credibility of the organizations and people who dared support them. Let’s look at how the CUTRIC example demonstrates Barnard’s use of every under-handed trick in his playbook to protect his narrative.

A Brief Overview of the Brampton Transit Study published by CUTRIC

The Canadian Urban Transit Research & Innovation Consortium (CUTRIC) published a study in Q2 of 2024 analyzing three different bus scenarios for Brampton in the Greater Toronto Area: battery electric only, hydrogen fuel cell only, and a mixed fleet of both technologies.[87] The study evaluated each scenario against key operational metrics including lifecycle costs, emissions, infrastructure requirements, and service reliability in a growing transit system. CUTRIC determined that the mixed fleet option struck the best balance, Mass Transit Mag quoted the study’s conclusion as the one that “best manages operational and financial risks by leveraging the strengths of both technologies while mitigating their individual weaknesses.”[88]

The reasoning was clear. Battery electric buses offer lower upfront costs and near-term deployment feasibility, particularly suited for lower demand and shorter routes. Hydrogen fuel cell buses deliver longer range and faster refueling performance, which is crucial for high utilization and cold weather operations. CUTRIC’s endorsement of a mixed fleet enhances operational resilience and aligns with Canada’s industrial strengths, including expanding domestic hydrogen production, fuel cell research, and bus manufacturing capabilities. This strategic alignment mirrors RMP’s organizational stance in favor of technology neutral, future resilient solutions that serve both environmental and economic priorities. That is: RMP supports batteries & hydrogen working together to tackle zero emission transit just like CUTRIC does.

Barnard Triggered by Brampton’s Plan

In Barnard’s 039 & 040 Podcasts titled “Buses – Hydrogen vs Batteries” parts 1 & 2 published in November 2024, we hear a conversation between Barnard and his friend Michael Raynor trashing the CUTRIC study and hydrogen in general. First and foremost, let’s address the title of the podcast. It is a common and clever technique of all anti-hydrogen influencers to frame hydrogen and batteries in competition rather than complimentary technologies that work well together. The technique of one ‘versus’ the other goads readers into thinking that only one technology can work and one must be discarded. Framing hydrogen & batteries as an “either/or” decision is one of the most universal tactics in every single anti-hydrogen post ever written. The idea is to reinforce the fallacy of a mutually exclusive mindset straight from the post’s very title.

Barnard lays out how he first became aware of the CUTRIC study while talking to his friend Raynor. Barnard says to Raynor “when you and I last spoke, yesterday or the day before, you were in your newest Tezzzla and stuck in traffic on highway 10 trying to get to the GO station”[18-1]. Raynor explained to Barnard that he first became aware of the Mississauga hydrogen bus initiative in 2022 and how he learned all he knows about hydrogen from Barnard and his band of influencers. Raynor says “Courtesy of linked-in I ended up tripping over your [Barnard’s] work and the clatch of anti-hopium folks from whom I’ve learned a great deal…pretty much close to…well, certainly the folks who pointed me in this direction. And now I feel I know enough to have an informed opinion about the relevant merits of hydrogen and battery powered electric vehicles.”[18-2]. Early on in the podcast we’ve learned Raynor has been educated about hydrogen from Professor Barnard at the University of Cleantechnica and even acknowledges Barnard’s sphere of ‘anti-hopium folks’ (i.e. Latour’s actors). Yet, when Barnard later writes about Raynor’s accreditation on the Cleantechnica post offering a transcript of the same podcast, he pumps Raynor’s resume up saying his views are “shaped by his Harvard doctorate of business administration, global business strategy career with Deloitte, and four books on strategy and innovation”[17-3]. Mr. Raynor says he learned about hydrogen buses from Barnard and friends, but Michael writes about Mr. Raynor’s credentials as if he’s an accredited bus expert. This intentionally misleads readers into thinking Raynor has better insight than CUTRIC as it relates to public transit. This is a common Barnard tactic: attack accredited institutions, and fabricate accreditation in supporters of his narrative.

Barnard’s triggers don’t really show until around the 25-minute mark of the podcast. One of the biggest triggers for Barnard is when a sovereign government puts tens of millions of dollars into a new hydrogen technology investment. When a hydrogen related investment in Western countries reaches into the billions, Barnard beams the kind of laser eyes you see in crypto memes. Keep this in mind when we get to Part 3 of this series which covers critical minerals. Michael never questions China’s massive state investment in the lithium-ion battery supply chain or in the polysilicon supply chain for solar panels and microchips. This is a key point, because it shows how Michael misleads most blatantly when the subject turns to money and economics.

Barnard rails against Canadian hydrogen technology company Ballard Power headquartered in his current home town and gets very animated: “So then we have Ballard Power the BC company which has managed to win $1.3B dollars or $55M/year on average since 2000 and has never turned a profit! And it’s been involved in fuel cell trial after fuel cell trial around the world. It’s sold fuel cells to China. it’s sold fuel cells to Europe. And ya know it’s selling fuel cells which end up in buses and vehicles which end up rusting in parking lots because the trials inevitably end up in failure!”[18-3]

Barnard is keen to denigrate Canadian companies like Ballard & New Flyer because they are competing to pioneer hydrogen fuel cell technology for the world which pits them directly against the anti-hydrogen narrative he supports. In this case, New Flyer is competing against heavily subsidized Chinese bus OEMs like Yutong Bus Company. Yet despite Yutong receiving millions more in government support than Ballard Power year after year for the past several years, Barnard never mentions it on a podcast or writes about it at Cleantechnica.[19] Barnard appears to only be triggered by Western companies receiving tax subsidies for hydrogen development.

Winnipeg-based New Flyer produces buses across multiple propulsion platforms including battery electric, hydrogen electric, diesel, and compressed natural gas. That deviation from Barnard’s battery-only narrative apparently earns his scorn. Since beginning research for this piece in June 2025, Barnard has published numerous posts including one especially abrasive example titled “Time For Canada To Dump The Big Three & Go Electric With China” published July 3, 2025. The post mostly libels Western automotive OEMs that have worked together with Canada for decades to provide good-paying jobs and a partnership with Canadian communities for over a century. Barnard suggests in the post to kick these Western companies out who have invested billions into Canada and replace them with Chinese automaker BYD. But let’s stay focused on buses and look at how Barnard disparages Canadian bus maker New Flyer in this same article. He suggests Canada should replace New Flyer with Chinese bus maker Yutong. While I recommend you read the entire post, let’s look specifically at this paragraph in Barnard’s own words:

“Canadian-made Yutong electric buses could rapidly replace the aging diesel fleet polluting our cities. They would be cheaper and far better than the inferior and expensive products from the other retrograde Canadian manufacturer, New Flyer, which continues to push diesel, CNG, and hydrogen buses instead of focusing on making superior battery electric transit vehicles. These are not futuristic fantasies; they are existing products waiting only for a willing partner in North America. Canada should leap at this opportunity rather than continue subsidizing complacency. Get Winnipeg on board by having the Yutong factory there employing the local skilled workforce that New Flyer isn’t putting on electric bus lines, or put Yutong in Bromont in Quebec, leveraging the skilled and international workforce there.”[20]

Barnard attacks New Flyer for “pushing” diesel, CNG, and hydrogen buses as if they were technological relics. But what about Yutong Bus Company’s product line? Yutong also makes diesel, CNG, and hydrogen buses. Heck, Yutong even makes buses that run on LNG. In fact, Yutong is only one of nearly a dozen Chinese bus makers receiving Chinese subsidies to make hydrogen buses while North America only has one: New Flyer. Why the disparate treatment? You only need to remember the tenets of the narrative: never support hydrogen & ignore or downplay anything China does that goes against the narrative. To reiterate, Barnard’s guns only aim west.

Yutong is doing the right thing, the same way New Flyer is doing the right thing: they’re making bus propulsion systems for different market segments that have different needs. Yutong is also doing what CUTRIC recommends, again, they’re making buses to fit the economic market realities of the world. If you get your education from Barnard, however, you’ll only get his skewed narrative supported by his fellow actors. A narrative that attacks North America’s only hydrogen bus maker for making hydrogen, diesel, and CNG buses while never attacking the nearly one dozen Chinese bus makers that make hydrogen, diesel, and CNG buses; it’s a double standard. Something is rotten.

Recycling Old Myths and Bad Data

To make his case against hydrogen buses, Barnard leans heavily on outdated and misleading comparisons. Central to all Barnard’s writings, he reiterates misleading information repeatedly until the reader or listener has heard it so many times, they accept it as true. He will float it on his podcast to his test market, usually a friend/actor (in this case Michael Raynor), then spawn articles off it. Then, he’ll go on someone else’s podcast and say it again. Like his podcast’s name mocks, Barnard truly is “Redefining Energy” with a misleading narrative.

Throughout the 039 & 040 Podcasts titled “Buses – Hydrogen vs Batteries” parts 1 & 2 Barnard alleges incompetence and impropriety regarding the CUTRIC Brampton hydrogen bus study. The CUTRIC study fairly assumed a six-to-seven-year replacement cycle for hydrogen fuel cell stacks. That is consistent with real world deployments and makes them roughly equivalent to the battery replacement schedules on battery electric buses. Ballard’s FCmove™ fuel cell stacks used in New Flyer buses surpass 30,000 hours of operation with over 97 percent module availability, potentially lasting up to a decade or exceeding one million miles in typical heavy-duty transit duty cycles.[21][22][23] Barnard calls CUTRIC’s figures misleading and instead tells listeners that hydrogen powertrains would need to be replaced every three years. He also hangs a significant portion of his economic argument against FCEBs with this false assertion. Here in Barnard’s own words he gets very loud and animated on his podcast as he demonstrates this reiterative style of pinning his thesis on incorrect facts:

“And how short a time were the fuel cells were lasting? [in the CUTRIC study]. Well, they have the same replacement time of 6 to 7 years for both in their study! So that’s two and a half times to three times difference! So a fuel cell bus, you’re going to replace the fuel cell over 15 years, 5 times. Not twice. Not Twice! And battery electric buses, if you’ve got a 15 year life cycle, well guess what? You’re going to replace the battery once. Not twice!”[3-2]

Not only does this incorrect and emotionally charged assertion come from decade old, obsolete, and cherry-picked data, Barnard presents it as a certainty in November 2024 while accusing CUTRIC of being the one misleading the public. That is the rhetorical sleight of hand Barnard uses repeatedly: dismiss modern data, recycle old anecdotes, then project the act of misleading onto others.

The same tactic shows up when Barnard discusses hydrogen bus operations in cold climates. His primary example is Whistler, British Columbia, a more than decade old demonstration project that used first generation fuel cell systems. Anyone with a genuine interest in new energy technology knows the Whistler fleet is ancient history in terms of fuel cell design. Current stacks are multiple generations ahead, with vastly improved cold start capability and reliability. Yet Barnard repeats the Whistler 2010-2014 fleet demonstration as if it is the definitive evidence that fuel cell buses “do not work in the cold” in November 2024. Again, Barnard uses information more than a decade old which is long past its relevancy and presents it as a current fact, and then projects the misleading label onto someone else; in this case CUTRIC, but the tactic is always the same.

It is also worth noting what Barnard does not say. Battery buses have their own cold climate issues that are widely documented. A Canadian Urban Transit Research and Innovation Consortium (CUTRIC) review notes that battery electric buses suffer range degradation in winter, forcing agencies to either purchase larger fleets to cover the same service or install auxiliary heating systems that burn diesel or natural gas to keep riders warm. For example, Winnipeg Transit reported that battery bus range in winter was most impacted and could drop by as much as 40 percent due to heating loads and subzero conditions and recommended diesel heaters to keep range from dropping to 60%.[24] These are important considerations as laid out in the CUTRIC study given Winnipeg has on average 193 days with temperatures below freezing. Similarly, the U.S. National Renewable Energy Laboratory found that battery buses in Minnesota required fossil fuel heating to maintain interior comfort, which cut into both emissions goals and cost savings.[25]

This matters because the narrative is not as simple as “battery good, hydrogen bad.” In some scenarios, particularly in cold weather cities, a smaller fleet of fuel cell buses could replace a larger fleet of battery buses that need backup heaters and additional units to maintain service levels. That is not a knock on batteries. It is an argument for a portfolio of tools rather than Barnard’s one size fits all approach.

Attacking CUTRIC Instead of the Evidence

Barnard’s rhetoric goes well beyond debating the technical merits of hydrogen buses. In Podcasts 039 and 040 Buses – Hydrogen vs Batteries Parts 1&2, as well as more than 14 accompanying articles spawned at Cleantechnica from this same podcast, he turns the CUTRIC Brampton study into a punching bag, accusing the consortium not just of being wrong but of being dishonest and incompetent. At one point in podcast 040 Barnard says:

“I look at that and I’d say, I personally, if I was a transit agency and looked at our findings, I would be seriously questioning CUTRIC’s incompetence, whether they were biased towards hydrogen. And I would be getting third party others to redo any numbers that CUTRIC had provided me because they’re not credible.”[3-3] And later: “If CUTRIC doesn’t improve this, they don’t have a reason to exist.”[3-4]

Those are not critiques. They are existential attacks, designed to brand an entire Canadian research consortium as unfit for purpose. That’s rotten.

Barnard does not stop there. In his CleanTechnica post titled “Deloitte Complicit In Indefensible Brampton Hydrogen Bus CUTRIC Study”[17-13], he expands the indictment to Deloitte & Touche, one of the world’s largest auditing and consulting firms. Barnard suggests Deloitte was “complicit” in pushing faulty numbers because they supported CUTRIC’s findings. To call Deloitte complicit is a serious allegation. It implies collusion, bias, and impropriety at the highest levels—all based on evidence easily demonstrated here to be misleading & unsubstantiated. Just earlier in Barnard’s stated accreditation of his friend Michael Raynor, he boasted about Raynor’s career at Deloitte, now he is alleging Deloitte is committing serious crimes, which they are not.

This is the pattern: Barnard creates an elaborate and prolific barrage of accusations to paint accredited professional institutions as not just mistaken, but corrupt. He uses misleading technical arguments to attack the CUTRIC study unfairly, he frames the entire exercise as incompetence at best and conspiracy at worst. The effect is never to advance discussion but to tarnish CUTRIC’s credibility and force them into a defensive posture, where they must waste energy responding to baseless allegations rather than focusing on technology development and deployment.

In short, Barnard’s strategy is not critique—it is narrative warfare. By targeting CUTRIC and even Deloitte with ungrounded claims of bias and complicity, he manufactures scandal where none exists. The result is an environment where Canadian transit innovation is maligned, Canadian expertise is dismissed, and the only “credible” voice left standing is Barnard himself. These attacks are not limited to CUTRIC, Barnard attacks anyone that doesn’t follow the four tenets of his narrative.

CUTRIC’s CEO Responds—Setting the Record Straight

In response to the barrage of Barnard’s attacks, CUTRIC’s CEO Dr. Josipa Petrunić took to LinkedIn with the post “Setting the Record Straight on the Strategic Role of Hydrogen in Canada’s Transit Future.” There, she defended the organization’s strategic approach, underscored the careful quantitative modeling behind their recommendations, and objected to what she characterized as personal attacks and straw-man criticisms. RMP could not agree more with CUTRIC’s (and Deloitte’s) positions on the study & its conclusions. I will post Dr. Petrunić’s response here in full so you can read it in her own words:

New technologies always produce controversy. Especially new “green” technologies. The clean tech industry has an uncanny ability to produce ideological positions even though the end goal for most folks involved in green technology innovation is usually the same – saving the human species from death-by-pollution.

At the Canadian Urban Transit Research & Innovation Consortium (CUTRIC) we believe no solution should be left off the table in the fight against complex climate change or in the transition to decarbonized transportation.

Ideology, angry rants and identity politics aimed at delegitimizing innovative technologies that aim to improve the environment or – worse – attempts at personalized defamation and character assassination against the individuals involved in thoughtful innovation, including myself and my team, do not help anyone. And they certainly do not help the environment.

In recent days, a series of opinion pieces published in CleanTechnica, written by author Michael Barnard, and a host of angry online postings on LinkedIn have railed against hydrogen as a viable transportation fuel for use in public transit systems in Canada.

These kinds of one-sided approaches are not new to CUTRIC. When we launched the Pan-Canadian Electric Bus Demonstration & Integration Trial with partners at the City of Brampton, York Region Transit and TransLink, a slew of online hatefulness followed full of vacuous arguments about how batteries would always fail, never be ideal or “clean” and never compete with hydrogen as the optimal transportation solution.

Rarely in life is there a single, clear solution to a complex problem. Clean transportation is no different. To focus solely on one technology (or to vilify one outside the context of application) is to discredit the power of the human mind to find solutions for even the most resistant complex problems, like transportation emissions.

Green technology innovation in public transit requires a 360 degree viewpoint – a willingness to see the full slate of benefits, limitations, revenues and costs associated with a new fuel or its associated infrastructure deployment.

Taking a holistic view means understanding that no technology – not battery electric, not hydrogen fuel cell and not even renewable natural gas – is the ideal solution in all circumstances all of the time. Each technology and allied fuel source comes with its own set of problems.

Sometimes battery electric buses and chargers do not communicate and they fail to initiate a charge. Sometimes charger pantographs fail to deploy. Sometimes batteries deplete and degrade faster than expected. Sometimes hydrogen dissipates, escapes and leads to lost revenues. Sometimes battery fires on both battery electric and hydrogen fuel cell buses happen. Sometimes things go wrong. Sometimes electricity is cheap but power is expensive. Sometimes cheap hydrogen is available but it’s dirty. Sometimes prices are nowhere near what an agency can afford whether it’s battery or hydrogen.

No new technology is immune from failure or economic constraints. We speak from direct experience with transit agencies in Canada that have gone through the trials and tribulations when launching their first electrified vehicle fleets.

Still today, some battery electric buses in British Columbia and Alberta have been down more than up – waiting for improvements and repairs to get back into operation. Some hydrogen fuel cell buses in North America have failed to turn on in the cold or have run out of power at the top of a hill and have had to sit while regenerating electricity onboard. It happens.

CUTRIC Zero Emissions Transit Fund (ZETF) analysis work is based on years of robust algorithmic and empirical analytical work with public transit agencies, utilities and manufacturers. The work has been vetted and validated by several agencies over and over. But like any modeling work, predictions are only as good as the input assumptions, which are unique to public agencies in many ways.

Our analysis tools explore – in standardized form – fully battery electric bus (BEB) solutions, fully hydrogen fuel cell electric bus (FCEBs) solutions, “mixed” green fleets with optimized balances of both technologies and renewable natural gas (RNG) solutions. We also explore smaller sized diesel and gasoline vehicles, including “on demand” models (i.e. Uber-type transit services), which can be better emissions saving tools than either battery or hydrogen buses. This is often the case in small agencies operating in more rural areas of Canada, where service areas are large but population and ridership may be low.

CUTRIC’s assessments of “mixed green fleet” assessments with the federal Zero Emissions Public Transit Fund (ZETF) highlight optimal balances between battery and hydrogen solutions for public transit based on local constraints that agencies (rightly) put in place.

Distances, road speeds, space to store vehicles, space to fuel or charge vehicles, real estate costs, schedule flexibility for downtime and dozens of other variables go into a modelling exercise. In the case of the City of Brampton, Brampton Transit had several conservative parameters that the CUTRIC team integrated in our modelling work. Some of those parameters include heavy limitations on schedule time availability. Brampton-specific limitations and system preferences for legitimate operations led to an optimized solution composed of a “mixed green” fleet of both battery and hydrogen electric buses. More agencies are likely to identify the same going forward.

In his critical remarks, Barnard posits that hydrogen buses are disproportionality expensive compared to battery-electric buses. He’s not wrong that FCEBs are expensive. But disproportion depends on the broader framework of total cost of ownership and operational complexities that agencies are working to avoid during electrification transitions. Our analyses do not show an evident disproportionately when factors like longer charging times for BEBs compared to faster fuelling times for FCEBs, or higher replacement ratios (more buses) for BEBs compared to lower replacement ratios (fewer buses) for FCEBs, are taken into account.

These complexities depend on real estate and depot space and the availability of hubs for networking opportunities with other agencies (e.g., shared hydrogen fuelling that multiple agencies can share).

Barnard and similar critics of hydrogen solutions often ignore these material issues of complexity as a driving force in selection of green technologies.

Cost is not the only factor or even the primary factor in many decarbonization plans. Complexity is equally important.

Emissions factors are also often lumped into one category. If it were this simple, climate change would have already been solved.

“Gray” hydrogen, produced from steam methane reformation, has a higher carbon footprint compared to “green” hydrogen, which is produced through electrolysis and which relies on Canada’s generally low-emissions electricity grid to produce. Our analyses provide comparisons of emissions from various hydrogen production methods ensuring that stakeholders have a realistic view of all types of hydrogen supplies that could feed into their buses.

Infrastructure costs are no different. The costs of hydrogen refueling for pilot deployments (say, 10 buses) can be very high due to low volume. Those costs come down as volume increases into thousands of kilograms per day and shifts from delivered hydrogen to on-site production or even piped hydrogen in the future.

Barnard’s assertion that battery-electric buses can meet all transit needs is scientifically ill informed. Battery electric buses are effective across large portions of fleet activity, but they cannot solve all transit needs. That statement is simply wrong.

BEBs face long charge times, including multi-hour in-depot charging episodes and extended five to 10 minute on-route charging episodes, which many transit agencies cannot fit into their current schedules without reblocking (which means more buses, more drivers and more cost).

CUTRIC’s work is always about modelling various scenarios to help agencies pick the best fit solution for their local circumstances and jurisdictional and operational realities.

In Brampton’s case, CUTRIC’s recommended “mixed green fleet” solution balances the total number of vehicles required as replacements (i.e., total number of BEBs over diesel) to achieve the same service level along with the additional labour hours required for charging and fuelling. This balancing act and set of calculations provides flexibility, complexity management and workforce hourly allocations alongside cost controls and infrastructure deployments both in depot and on route.

CUTRIC stands by its commitment to science over sales, and evidence before ideology.

Decarbonization strategies for public transit are not one-size-fits-all. An informed and balanced understanding of the issues shows that this is true in every municipality in this country.

We invite stakeholders to engage in constructive discussions to refine collective strategies for a sustainable transit future in Canada. We also invite them to avoid destructive narrow mindedness.

The path to decarbonization is a collaborative effort.

Addressing climate change requires we’re aware there is no such thing as a panacea in green energy. Hydrogen, battery electric and renewable natural gas will all be part of the solution spectrum the nation deploys in its drive to a sustainable, zero emissions future.[26]

The picture that emerges from Barnard’s podcasts and articles is not one of fair critique, but of targeted narrative warfare. By leaning on outdated data, resurrecting long-disproven case studies, and branding CUTRIC and even Deloitte as incompetent or complicit, Barnard constructs a storyline where hydrogen buses are doomed, and anyone who supports them is either biased or dishonest. Yet the reality is far more balanced: both hydrogen fuel cell electric buses and battery electric buses have strengths and weaknesses, and both are already serving different market needs across Canada, the U.S., Europe, and Asia. Barnard’s barrage of accusations does not advance clean transit—it distracts from it and undermines global innovation at a critical time.

But buses are only part of the story. The question of how hydrogen and batteries can best complement each other becomes even more important when we move beyond municipal transit into the world of heavy-duty trucking. Unlike urban buses, which can return to depots daily and recharge overnight, long-haul trucks face range demands, refueling constraints, and duty cycles that are far less forgiving. This is where hydrogen has long been viewed as a practical partner technology to batteries rather than a competitor. As we turn the page from transit to freight, the stakes only grow larger: billions in infrastructure, critical mineral supply chains, and the backbone of North America’s logistics network.

Class 8 Truck Electrification – Why Hydrogen and Batteries Must Work Together

Barnard’s treatment of heavy-duty trucking mirrors the same playbook he applies to buses: declare hydrogen unnecessary, inflate the promise of batteries, and trivialize the complexity of real-world infrastructure. In Podcast 005 “Charging Ahead: Overcoming Infrastructure Challenges in Electrifying Road Freight”, joined by his close ally/actor David Cebon, founder of the [anti] Hydrogen Science Coalition, Barnard frames the solution as obvious and even “trivial.” The two promote the idea that Class 8 trucks across North America can be easily outfitted with pantographs to connect to overhead wires—raising and lowering the pantograph to dodge bridges, tunnels, and gaps in the line—with batteries filling in the rest. Barnard also leans on the Tesla Semi (which has no pantograph) as his proof that the Class 8 problem is already solved. Yet the Tesla Semi remains an unverified prototype with no independent validation of its range, payload, or cost claims. What Barnard offers, then, is not a credible solution for a continent-spanning freight network but a fantasy built on untested assumptions and marketing promises from a company who is notorious for failing to deliver on promises. In the sections ahead, we’ll examine how this pantograph-and-battery vision collapses under scrutiny and how Barnard’s report The New Logistics doubles down on the same unsupported narrative.

Barnard & Cebon’s Pantograph-and-Battery Fantasy

David Cebon himself has openly acknowledged that installing catenary lines for rail would cost roughly £1 million per kilometer (about $2 million per mile)[15-2] as mentioned previously in the section on rail and from the very same podcast. That figure alone shows just how far from “trivial” this solution really is. America’s Interstate Highway System spans nearly 50,000 miles, and while no one is suggesting every mile would need catenary, even electrifying a fraction of major freight corridors for trucks, which would likely cost even more per mile than rail, would quickly balloon into the tens of billions of dollars. Achieving this would demand that multiple companies and government authorities across the United States align politically and operationally on both batteries and catenary deployment — an outcome that is highly improbable. Unlike dedicated rail lines, which already operate with controlled rights-of-way, highways run through thousands of jurisdictions—each with its own permitting regimes, land-use restrictions, and political challenges. Reconciling such massive construction projects across state borders and county commissions is anything but easy or “trivial” as Barnard calls it repeatedly.

In Podcast 005 – “Charging Ahead: Overcoming Infrastructure Challenges in Electrifying Road Freight”, Barnard casually brushes these realities aside. With his trademark dismissiveness, he says: “It’s actually quite easy infra structurally in the US because they’ve got – you just put them [megawatt chargers] at the intersections of a couple of interstates and – you plug a lot of power in there… It’s not hard to do.”[15-3] In one sweeping run-on sentence, the immense complexity of interstate infrastructure planning is reduced to a hand-wave from a microphone in Vancouver. The problem is that what sounds simple in theory is impossibly difficult in practice. States do not share unified permitting regimes, utilities do not automatically deliver multi-megawatt power wherever you ask, and freight networks are not neatly contained to “a couple of interstates.”

Even if we momentarily set aside the astronomical capital costs and permitting hurdles, the logistical headaches of downtime during construction are immense. Highway lanes would need to be closed for long stretches, traffic diverted, and freight disrupted across already congested corridors. Cebon himself concedes the massive price tag, but Barnard’s eagerness to trivialize the problem shows either a lack of appreciation for on-the-ground realities or a willingness to gloss over them to preserve his narrative.

All of this highlights the core issue with Barnard and Cebon’s pitch: it is not just about whether pantographs and batteries are technically possible—it is about whether they are economically and politically feasible at scale in North America. When a solution carries a greater than $2 million per mile price tag, requires navigating a patchwork of state and local governments, and demands cooperation from dozens of utilities and regulators, calling it “trivial” is not analysis, it’s wishful thinking.

Barnard Trivializes Challenges of Charging Infrastructure for Heavy Duty Trucks

Barnard applies the same “not hard to do” logic to nationwide charging networks for Class 8 trucks. In his telling, all that is required is placing megachargers at key interstate intersections and the problem is solved. But megawatt-scale charging is not the equivalent of installing a few gas pumps. Again I must reference my article debunking Liebreich’s Ladder when Liebreich interviewed Chargpoint CEO Pasquale Ramano when Pasquale said “There is usually transmission lines [sic] coincident with America’s highways, that’s the good news. Here’s the bad news: there’s no distribution coincident with highways. If you’re at a truck stop, you can look out your window and see megawatts! but you can’t get at it. Not without building a substation purpose built to tap into that transmission infrastructure for those megawa… there aren’t megawatts available”(source video below).

Dropping in charging locations or catenary infrastructure demands grid upgrades on a staggering scale: new substations, high-voltage transmission, transformer capacity, and utility coordination that often takes years, if not decades. Permitting timelines for transmission projects in the U.S. routinely stretch 7–10 years, and that is without the added complexity of siting charging depots for long-haul freight. What Barnard describes as trivial would in reality be one of the most difficult infrastructure challenges the U.S. has ever faced for trucks that do not yet exist and would be underpinned with Chinese supply chains. Barnard’s take on the topic is exactly the same as Liebreich’s: glossing over serious fatal errors.

Part of the sleight of hand here is cost framing. Barnard likes to compare hydrogen trucks—still a nascent technology—with battery trucks and even diesel, presenting the latter as cheaper and therefore destined to win. This logic is purposely misleading to fit his narrative. Comparing mature, globally scaled fossil technologies with emerging alternatives is apples-to-oranges. Battery trucks themselves are still reliant on subsidized Chinese supply chains for refined metals and components. Pretending these costs will continue falling indefinitely without addressing upstream constraints on lithium, nickel, cobalt, and LFP powder is not economics—it is outsourcing U.S. energy security to a foreign entity of concern. We will cover critical minerals further in Part 3 of this series to delve deeper into this important topic. For America to control its own destiny in freight, both battery and hydrogen pathways will require massive investment in the upstream, midstream, and downstream supply chains. Declaring one pathway “cheap” simply because of today’s market distortions is dangerously shortsighted.

Barnard’s White Paper: Overconfidence in a Battery-Only Microgrid Strategy

Barnard’s The New Logistics: Electrifying Freight with Microgrids is a polished 102-page whitepaper, but its substance does not live up to its form. The first thing any reader should notice is the absence of footnotes or source citations. For a document that pretends to look like a substantive white paper that makes sweeping claims about the future of freight, this omission of any citations speaks volumes. Instead, the report leans heavily on glossy graphics, professional layout, and authoritative-sounding assertions. Style substitutes for rigor, leaving readers with the impression of inevitability without the evidence to back it up

From the very first pages, Barnard insists that battery-electric freight dominance is a “foregone conclusion” [p.4]. Yet, by page 15, he highlights statistics showing battery trucks remain “statistically insignificant” in the broader freight market. These contradictions set the tone: a confident narrative unsupported by consistent data. By page 17, Barnard goes further, claiming electric trucking will soon undercut not only diesel, but also rail and marine freight — a breathtaking prediction offered without a single hard reference to infrastructure costs, operating constraints, or duty cycle limitations.

This short two and a half minute video clip from KCRA News (August 20, 2024) shows a Tesla Semi prototype that went off the road on Interstate 80 in Nyack, California. The fire required over 50,000 gallons of water to extinguish and burned through the night, shutting down the freeway and causing traffic backups for over 16 hours. It was a multi-agency fire fighting effort that included multiple air drops of fire retardant. A hazmat team lifted the charred remains of the truck from the forest and placed it on a flatbed diesel semi-truck for removal & transport back to the Giga Factory in Sparks, Nevada.

Equally problematic is Barnard’s reliance on the Tesla Semi as a proof point. He cites Tesla’s claimed performance metrics and suggests these vehicles are already redefining the trucking landscape [p.42]. But the Tesla Semi does not exist in any meaningful commercial volume. Its launch is now 8 to 9 years behind schedule, with no independently verified data to back Tesla’s or Barnard’s assertions. This follows a familiar pattern: Tesla has a long track record of overpromising — from the still-unrealized second-generation “flying” Roadster to the perpetually “next year” since 2014 timeline for full self-driving. Hanging an entire logistics thesis on a truck that has failed to materialize at scale and is 8 to 9 years past its promised series production SOP date is not just optimistic; it undermines the credibility of the argument itself.

Barnard’s New Logistics report leans into the Tesla Semi as a proof of battery powered Class 8 technology being decided, but it’s obviously not the only place he praises this vehicle that does not exist in series production 8 to 9 years after its promised delivery date. One of Barnard’s favorite catchphrases across his podcasts is “fit for purpose.” He often uses it as a conversation stopper, shutting the door on anything that challenges his narrative. In plain terms, fit for purpose means “suitable for the task it’s supposed to perform.” Read this Barnard quote from podcast 005 with his colleague David Cebon as an example: “So, right now, Tezzzzla Semi, working for Pepsi, it’s going, it’s taking flats of Pepsi, fully loaded 400 miles, 640 kilometers in a single journey. So we’re already fit for purpose with that technology, an optimized electric truck”[15-4] That quote is from a June 2023 Barnard podcast. Barnard said that on his podcast two years before he published his The New Logistics report in April 2025; the truck is still not in production in October 2025. The Tesla semi is almost 9 years late now. The Tesla Semi is a far way from ‘fit for purpose’, it doesn’t even exist in the market place.

Infrastructure and Scaling Challenges in The New Logistics

Barnard’s report consistently downplays the monumental infrastructure required for battery-electric trucking at scale. On page 24, he writes: “Only 203,000 semi trucks were sold in 2023, a volume which can easily pivot to battery electric and grow rapidly.” This oversimplifies decades-long industrial transitions and ignores the constraints of upstream material supply. Scaling a battery fleet requires massive investment in lithium, cobalt, nickel, manganese, and LFP powder supply chains — industries that cannot pivot overnight and require billions of dollars and years of development.

The Maersk microgrid in Denker near the Port of Los Angeles, is cited throughout Barnard’s report as a model for success. Barnard presents it as a battery-only solution, but the system currently uses natural gas turbines for generation which Barnard does not mention in his 102 page paper. Even more telling, Maersk’s own documentation notes these turbines at Denker are designed to run on hydrogen in the future.[27] By omitting this, Barnard erases the hybrid nature of real-world energy solutions and creates the illusion that battery-only systems are sufficient today. You have to wonder how Barnard cites his key anti-hydrogen microgrid thesis without mentioning Maersk specifically emphasized the turbines were ‘hydrogen-ready linear generators’; it is a profound oversight demonstrating Barnard’s lack of due diligence.

Additionally, Barnard’s repeated claim that “no site is unique” [p.71] or that microgrids can simply scale like LEGO blocks [p.72] trivializes the realities of U.S. logistics. Every site has unique zoning laws, utility connections, land availability, and operational needs. Pretending all depots can adopt the same modular solution ignores the regulatory, engineering, and physical constraints inherent in large-scale deployments. This is exactly the same short-sightedness Dr. Petrunić scolded Barnard for when she was forced to respond to Barnard’s attacks.

Hydrogen’s Role Overlooked in Barnard’s Microgrid Vision

Finally, by page 55, the elephant in the room shows up: diesel fuel will be necessary ‘just in case’. Buried deep in the report, Barnard acknowledges that diesel will still play a role in smoothing over shortfalls in solar-powered charging. This admission undercuts the very premise of his “new logistics” model. If the strategy relies on fossil fuels, especially diesel, to paper over gaps in renewables, then it is neither new nor sustainable. Worse, it reveals a blind spot in Barnard’s economic reasoning: the goal of hydrogen adoption is precisely to displace diesel at scale, providing a low-carbon backup for intermittent renewables. Ignoring that dimension doesn’t make it go away; it just exposes the fragility of a battery-only argument. Hydrogen can fulfill the exact role Barnard’s model still relies on diesel for—storing energy seasonally, displacing fossil fuels, and ensuring reliability in a decarbonized grid. These technologies must work together, there is no single solution for an industry as complex as energy.

Ignoring hydrogen removes a complementary technology already acknowledged in real-world systems, like Maersk’s hydrogen-capable turbines that Barnard incredibly somehow did not notice or mention in his report. It also undermines the economic and operational resilience of battery-only plans, especially given the geopolitical and supply-chain risks associated with importing all batteries and solar panels from foreign entities. Barnard’s treatment presents a singular, overly confident pathway, when the reality is that hybrid solutions — batteries plus hydrogen — are already emerging as the most practical route to sustainable freight.

By combining omissions, oversimplifications, and reliance on unverified prototypes like the Tesla Semi, Barnard’s battery-only vision presents a misleadingly easy path forward. The report’s polished look masks the fragility of its assumptions, ignoring both the technical and strategic complexity required to scale electric freight across North America.

As we conclude Part 2 of this series regarding the technological and operational challenges of sustainable transportation, no discussion about the future of mobility is complete without considering the supply chains that underpin it. Part 3 of this series will focus on the critical minerals—lithium, cobalt, nickel, rare earth elements, and others—that form the backbone of batteries, fuel cells, and other key technologies. Control over these resources shapes not only production costs and timelines but also the strategic autonomy of nations seeking to decarbonize.

Part 2 of this series has highlighted how North American companies and policymakers must navigate both technical complexity and market realities for heavy duty transportation. In parallel, the global distribution of critical minerals presents another layer of challenge: securing reliable, sustainable, and ethically sourced materials while maintaining a level playing field. It is essential to recognize the competitive practices of other nations, particularly when state-backed strategies may create advantages that distort global markets. At the same time, it is equally important to advocate for fairness, transparency, and mutually beneficial cooperation, ensuring that no country is forced to compromise its energy security or innovation potential.

In Part 3 of this series, we will examine the intersection of critical minerals and intellectual property, exploring how supply chains, technology ownership, and industrial policy converge to shape the future of clean energy in North America and globally. Part 3, the final part of this series, will be published next Sunday, stay tuned.

Footnotes:

Footnote [3] – Michael Barnard (Host), Michael Raynor(Guest). “40: Buses – Hydrogen vs Batteries (2/2)” Redefining Energy – TECH, no. 40, 20 November 2024, https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/40-buses-hydrogen-vs-batteries-2-2/id1675126007?i=1000677634349. Accessed 27 September 2025.

Footnote [3-2] – 02:14 – Michael Barnard says “And how short a time fuel cells were lasting? [in the CUTRIC study]. Well, they have the same replacement time of 6 to 7 years for both in their study. So that’s two and a half times to three times difference. So a fuel cell bus, you’re going to replace the fuel cell over 15 years, 5 times. Not twice. Not Twice. And battery electric buses, if you’ve got a 15 year life cycle, well guess what? You’re going to replace the battery once. Not twice.”

Footnote [3-3] – 44:12 – Michael Barnard says about CUTRIC’s Brampton bus study “I look at that and I’d say, I personally, if I was a transit agency and looked at our findings, I would be seriously questioning CUTRIC’s incompetence, whether they were biased towards hydrogen. And I would be getting third party others to redo any numbers that CUTRIC had provided me because they’re not credible”

Footnote [3-4] – 44:46 – Michael Barnard says about the Brampton bus study “If CUTRIC doesn’t improve this, they don’t have a reason to exist”

Footnote [14] – Association of American Railroads (AAR). “Study Confirms Catenary System Infeasible for U.S. Freight Rail Network” AAR, 26 February 2025, https://www.aar.org/news/study-confirms-catenary-system-infeasible-for-u-s-freight-rail-network/. Accessed 27 September 2025.

Footnote [15-1] – Michael Barnard (Host), David Cebon (Guest). “5. Charging Ahead: Overcoming Infrastructure Challenges in Electrifying Road Freight (1/2)” Redefining Energy – TECH, no. 5, 7 June 2023, https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/5-charging-ahead-overcoming-infrastructure-challenges/id1675126007?i=1000616000189. Accessed 27 September 2025.

Footnote [15-1] – 20:10 – Michael Barnard says about US rail planners “It’s quite remarkable that they’re so out of step with the obvious solution.” with regard to catenary rail in the USA which the AAR considers uneconomic for reasons cited.

Footnote [15-1] – 20:10 – David Cebon says “It is quite shocking” as he agrees with Barnard’s comment above.

Footnote [15-2] – 20:49 – David Cebon says about the cost of installing catenary infrastructure in the UK: “These are incredibly conservative industries. But this is some interesting stuff. In the UK, it costs about a million pounds per kilometer to put up caternary cables on railway lines. The project costs are actually three times that.”

Footnote [15-3] – 40:49 – Michael Barnard says “It’s actually quite easy infra structurally in the US because they’ve got – you just put them at the intersections of a couple of interstates and – you plug a lot of power in there… It’s not hard to do. And mega chargers, you know, the Tesla mega charger returns 70% of the battery charge in 30 minutes. Right.”

Footnote [15-4] – 29:28 – Michael Barnard says “So, right now, Tezzla Semi, working for Pepsi, it’s going, it’s taking flats of Pepsi, fully loaded 400 miles, 640 kilometers in a single journey. So we’re already fit for purposewith that technology, an optimized electric truck”

Footnote [16] – Michael Barnard (Host), David Cebon (Guest). “6. Charging Ahead: Overcoming Infrastructure Challenges in Electrifying Road Freight (2/2)” , no. 6, 22 June 2023, https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/6-charging-ahead-overcoming-infrastructure-challenges/id1675126007?i=1000617966033. Accessed 27 September 2025.

Footnote [16-1] – 11:07 – Michael Barnard says “Putting a pantograph on the roof to feed those electric motors is a trivial addtion. And dropping a container car of batteries just behind the locomotive to feed those motors is a trivial change”

Footnote [16-2] – 28:48 – Michael Barnard says “I’ll give a very brief explanation of the learning cureve. It’s a sigmoid. it’s one of those classic S-shaped curves. It was first discovered by a gentleman named Wright, an efficiency expert in the 1920’s or 1930’s. And he observed that with every doubling of manufactured units, the per unit went down by 20 to 27 percent. And Boston Consulting Group called it the experience curve. Other peole called it the learning curve.”

Footnote [17] – Barnard published the following 14 articles at Cleantechnica libeling CUTRIC and disparaging Canada’s transit planners after his conversation with Michael Raynor in October 2024 which became a podcast with Raynor published November 2024:

17-1: Canadian City About To Buy Hydrogen Buses Because Feds & CUTRIC Captured by Hydrogen Lobby (Oct 15 2024)

17-2: Mississauga Could Get A Dozen Electric Buses For The Cost Of Five Hydrogen Ones (Oct 17 2024)

17-3: CUTRIC’s Hydrogen Bus Study Dodges $1.5 bn In Costs To Justify Higher Emissions (Oct 23 2024)

17-4: How Many Hydrogen Transit Trial Failures Are Enough? (Oct 24 2024)

17-5: New Flyer Bus OEM Has Its Strategy Wrong & Will Lose Market Share (Oct 28 2024)

17-6: How Many Things Can A Bus Transit Study Get Wrong? (Nov 6 2024)

17-7: Canadian Transit Think Tank CUTRIC Chooses Inaccuracy, Irrelevancy, & Attack (Nov 10 2024)

17-8: Agenda Of Canadian CUTA Transit Conference Shows They Have Hydrogen On Brain Too (Nov 18 2024)

17-9: Canadian Transit Think Tank CUTRIC Riddled With Conflicts Of Interest (Nov 19 2024)

17-10: Vancouver Translink Bus Decarbonization At Risk From $1.3 Million CUTRIC Sole Source Study (Nov 20 2024)

17-11: Winnipeg Is Making Major Local Transit Bus Firm New Flyer More Likely To Fail (Nov 21 2024)

17-12: How Can A Canadian Transit Think Tank Be So Deeply Incompetent? (Nov 23 2024)

17-13: Deloitte Complicit In Indefensible Brampton Hydrogen Bus CUTRIC Study (Dec 16 2024)

17-14: Canadian Transit “Think” Tank Presenting Fluff & Denials To Mississauga Council (Feb 3 2025)

Footnote [18] – Michael Barnard (Host), Michael Raynor(Guest). “39: Buses – Hydrogen vs Batteries (1/2)” Redefining Energy – TECH, no. 39, 6 November 2024, https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/39-buses-hydrogen-vs-batteries-1-2/id1675126007?i=1000675912730. Accessed 27 September 2025.

Footnote [18-1] – 20:39 – Michael Barnard says “when you and I last spoke, yesterday or the day before, you were in your newest Tezzzla and stuck in traffic on highway 10 to get to the GO station”

Footnote [18-2] – 19:02 – Michael Raynor says “Courtesy of linked-in I ended up tripping of your [Barnard’s] work and the clatch of antihopium folks from whom I’ve learned a great deal…pretty much close to…well, certainly the folks who pointed me in this direction. And now I feel I know enough to have an informed opinion about the relevant merits of hydrogen and battery powered electric vehicles.”

Footnote [18-3] – 26:12 – Michael Barnard says “So then we have Ballard Power the BC company which has managed to win $1.3B dollars or $55M/year on average since 2000 and has never turned a profit. And it’s been involved in fuel cell trial after fuel cell trial around the world. It’s sold fuel cells to China. it’s sold fuel cells to Europe. And ya know it’s selling fuel cells which end up in buses and vehicles which end up rusting in parking lots because the trials inevitably end up in failure.”

Footnote [19] – Global Trade Alert. “China: Government subsidy changes for listed company Zhengzhou Yutong Bus Co.,Ltd. in year 2020” Global Trade Alert, 1 January 2020, https://globaltradealert.org/state-act/54434. Accessed 7 October 2025.

Footnote [20] – Michael Barnard. “Time For Canada To Dump The Big Three & Go Electric With China” CleanTechnica, 3 July 2025, https://cleantechnica.com/2025/07/03/time-for-canada-to-dump-the-big-three-go-electric-with-china/. Accessed 27 September 2025.

Footnote [21] – Ballard Power Systems. “923-9 Mission Innovation: Ballard Power Systems” US Department of Energy, 1 December 2021, https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2021-12/923-9-mission-innovation-ballard.pdf. Accessed 7 October 2025.

Footnote [22] – Ballard Power Systems. “FCmove™-HD Fuel Cell Power Module for Heavy Duty Motive Applications” FC Nexus, 1 June 2019, https://hfcnexus.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Ballard-FCmove-data-sheet.pdf. Accessed 7 October 2025.

Footnote [23] – Ballard Power Systems. “FCmove®-XD Fuel Cell Engine with Class-Leading Power Density” Fuel Cells Works, 21 August 2024, https://fuelcellsworks.com/news/ballard-introduces-new-scalable-fcmove-xd-fuel-cell-engine-with-class-leading-power-density-at-iaa-transportation-2024. Accessed 7 October 2025.

Footnote [24] – Winnipeg Transit. “Transition to Zero-Emission Technology Report – Rev1” Winnipeg Transit, 14 January 2021, https://info.winnipegtransit.com/assets/2788/Transition_to_Zero_Emission_Technology_Report_-_Rev1.pdf. Accessed 7 October 2025.

Footnote [25] – U.S. Department of Energy. “Cold Weather Impacts on Battery-Electric Transit Buses” DriveElectric.gov, 1 May 2024, https://driveelectric.gov/files/transit-cold-weather-help-sheet.pdf. Accessed 7 October 2025.

Footnote [26] – Josipa Petrunic. “Setting The Record Straight: Strategic Role Of Hydrogen” she / elle (LinkedIn), 8 November 2024, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/setting-record-straight-strategic-role-hydrogen-petrunic-she-elle–dnhjc/. Accessed 27 September 2025.

Footnote [27] – Performance Team – A Maersk Company & Prologis. “A Maersk Company and Prologis Launch New EV Truck Charging Depot” Prologis / Maersk News, 23 May 2024, https://www.maersk.com/news/articles/2024/05/23/maersk-and-prologis-launch-new-ev-truck-charging-depot?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Accessed 7 October 2025.

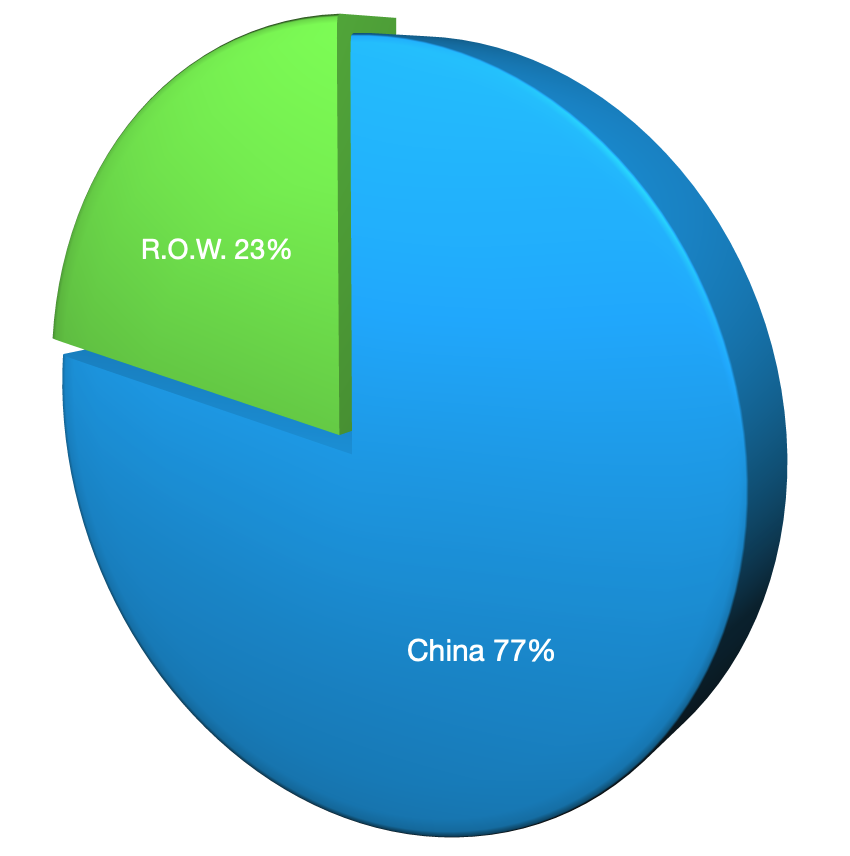

Footnote [86] – International Energy Agency. “Global Hydrogen Review 2025.” International Energy Agency, July 2025, https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2025 . Data indicate an estimated 77 % of the world’s hydrogen fuel-cell buses are in China and 23 % in the rest of the world (global total ≈ 11 000 units). Accessed 12 October 2025.

Footnote [87] – Canadian Urban Transit Research & Innovation Consortium (CUTRIC). “ZEB Implementation Strategy & Rollout Plan – Summary Report” CUTRIC, 1 April 2025, https://cutric-crituc.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/ZEB-Implementation-Strategy-and-Rollout-Plan-Summary-Report-CUTRIC.pdf. Accessed 7 October 2025.

Footnote [88] – The Canadian Urban Transit Research & Innovation Consortium (CUTRIC). “Latest CUTRIC report details zero-emission bus implementation plan for Brampton Transit” Mass Transit Mag, May 9 2024, https://www.masstransitmag.com/bus/vehicles/hybrid-hydrogen-electric-vehicles/press-release/55038606/the-canadian-urban-transit-research-and-innovation-consortium-cutric-latest-cutric-report-details-zero-emission-bus-implementation-plan-for-brampton-transit. Accessed October 7 2025.

Leave a Reply